Royal Burial and the Chronology of Egypt at the Birth of the Egyptian State

The Pottery from Abydos Cemetery B

A project run under the auspices of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo

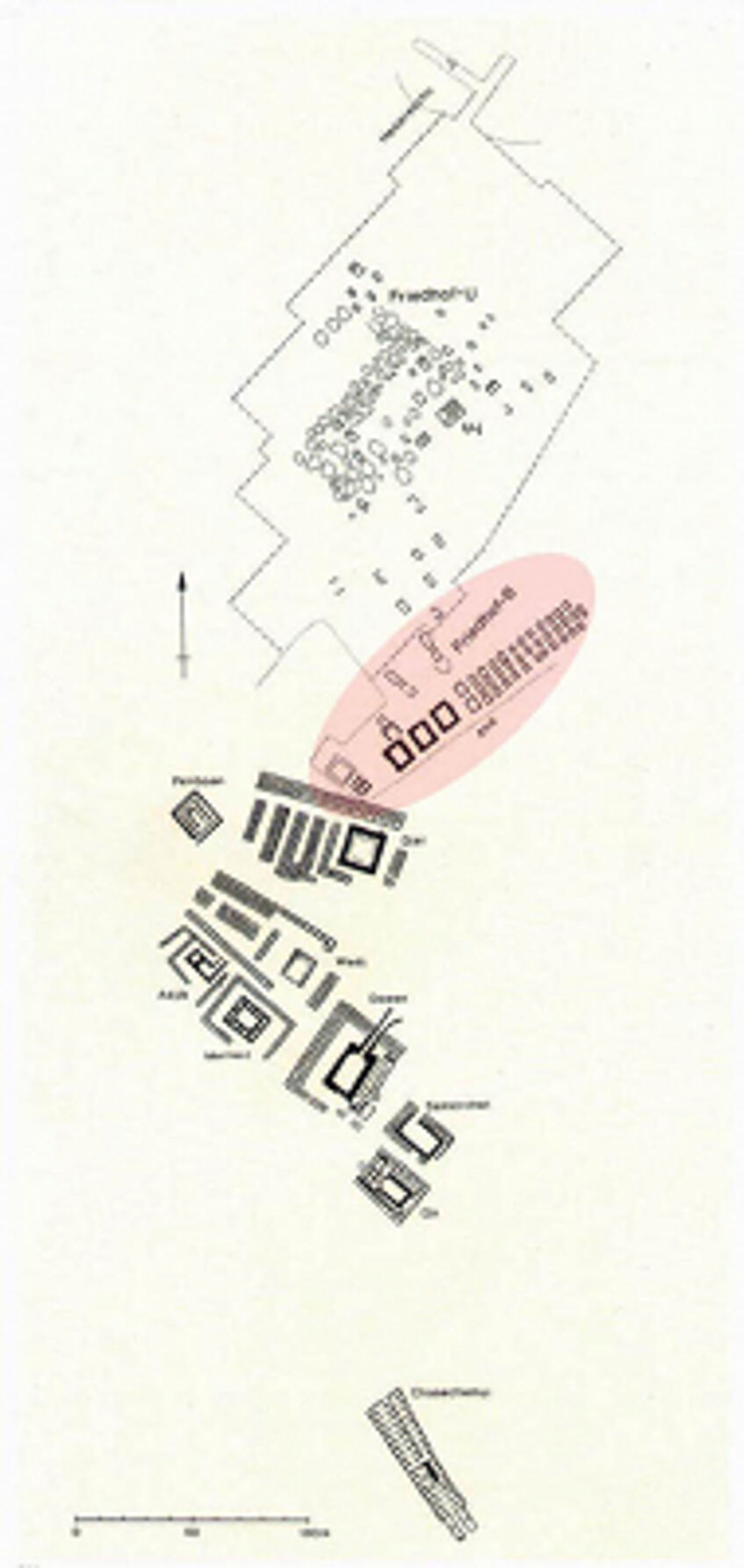

The B Cemetery at Abydos forms a discreet portion of the Early Dynastic Royal Cemetery at Abydos. Bordered to the local northeast by the pre- and protodynastic tombs of cemetery U and to the local-west by the enormous tomb complex of King Djer, the third King of Dynasty 1, the B Cemetery occupies an important spatial and chronological position in the sequence of royal burials at the dawn of the Egyptian territorial state (Figs. 1, 2). The Cemetery comprises five separate tomb complexes of Dynasty 0 and the early First Dynasty (Naqada IIIB-C1). The ownership of these tombs, proposed on the basis of inscriptions found within and in the environs of the tombs themselves include Iri-Hor (=Tomb B0/1/2) and Ka/Sekhen (=Tomb B7/9), both rulers of so-called Dynasty 0, as well as Narmer (possibly B17/18) and Hor Aha (B10-19 excluding B17/18), possibly the first two kings of Dynasty 1 and perhaps the first kings to rule all of Egypt. The ownership of the fifth tomb complex (B40/50) remains more problematic and is the subject of on-going research.

Introduction

After initial excavation by E. Amélineau and W.M.F. Petrie, the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo has been conducting investigations in Cemetery B since 1977 under the direction of W. Kaiser and G. Dreyer. This later research focussed on the systematic re-excavation of already known tombs and also revealed a previously unrecorded structure B40/50.

Apart from the re-excavation and architectural re-assessment of the tomb structures the new investigations also engaged in the sifting of the extensive mounds of excavation spoil surrounding Cemetery B, which allowed for a collection of artefacts, especially of pottery fragments, not kept by the previous excavators and presumably belonging to the tombs in this cemetery. This work has now come to completion and the German Institute is preparing this material for publication.

Fig. 1: Plan of Umm el-Qaab with B Cemetery emphasized (Plan ©DAIK)

In addition to numerous stone vessel fragments, the greatest proportion of grave contents of the early royal tombs were pottery vessels, used as containers for various commodities stored in the tombs, such as wine, beer and oil. E. Christiana Köhler and Christian Knoblauch of the University of Vienna have been entrusted with the recording, analysis and publication of this important corpus of material since 1991, and 1999 respectively. The documentation stage of the work was completed in early 2013 and the phase of evaluation, analysis and, eventually, publication has now commenced.

Fig. 2: View of the B Cemetery looking west (in the fore ground right the rock-marked pits of B0-2 are visible)

Problems and Possibilities

The German excavations are by no means the first excavations in the B Cemetery. Already in antiquity the tombs were likely to have been the subject of repeated and intensive periodic looting, and in modern times, the majority with very few exceptions, were completely excavated and studied by both Amélineau and Petrie. Understandably, these transformation processes have resulted in the wide dispersal of the original tomb contents over the entirety of the B Cemetery, and even beyond its borders into Cemetery U and the tombs of Djer, Den and Peribsen. The material original to the B Cemetery is mostly found in excavator’s backfill in tomb chambers or, as is more common, in the massive “spoil heaps”, the discarded excavation debris from earlier times that dominated the modern landscape of Umm el-Qaab until recently. Only in very rare exceptions have vessels been recorded in-situ and in a reliable archaeological context.

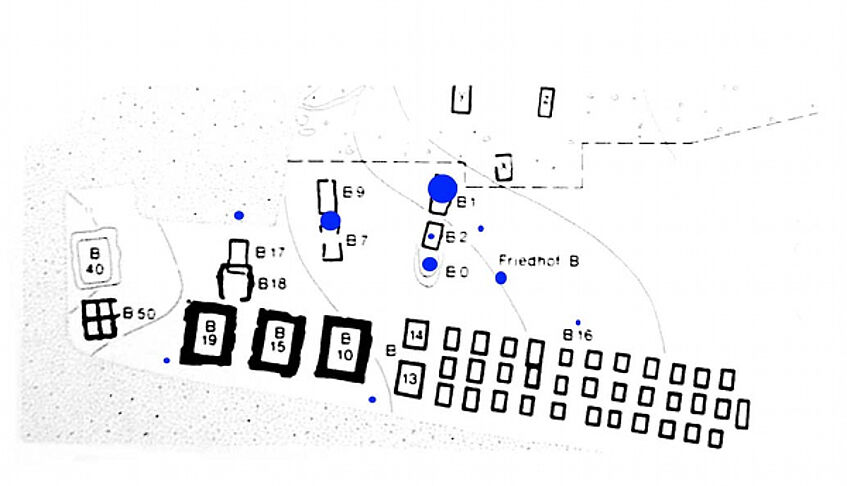

Given this problem, it is almost impossible to trace individual pottery vessels with certainty to a particular tomb complex, let alone a certain tomb chamber. The distribution map of the sherds belonging to one so-called “wine jar” (No. 3; Figs. 3, 4) illustrate this problem well. Painstakingly reconstructed from 68 sherds, one can immediately see that the origin of the material from this one vessel includes the whole of the B Cemetery. A concentration of material from one area of the cemetery may conceivably be taken to indicate the original location of the jar in question, but this is highly speculative.

Fig. 3: Distribution map of "Wine jar" No. 3 (the size of each dot indicates the number of fragments)

Fig. 4: "Wine jar" No. 3 after reconstruction

Fig. 5: Example of a reconstructed cylindrical vessel with Decoration Type 633

Nonethelesss, by combining qualitative research of fabrics and vessel morphology with quantitative documentation and analysis of all the diagnostic material, it is possible to get maximum information from this poorly contexted, and remarkably badly preserved material. It is certainly worth the effort: On the one hand, the material provides an insight into the nature of royal burial customs of the first Egyptian kings. On the other hand, it illustrates diachronic trends in pottery production during Dynasty 0 and early Dynasty 1 (Naqada IIIB-C1). It is therefore potentially crucial data for refining the ceramic-based relative chronology of Egypt (or at least for the Abydos region) as well as linking this chronology with the historical chronology of early Egypt.

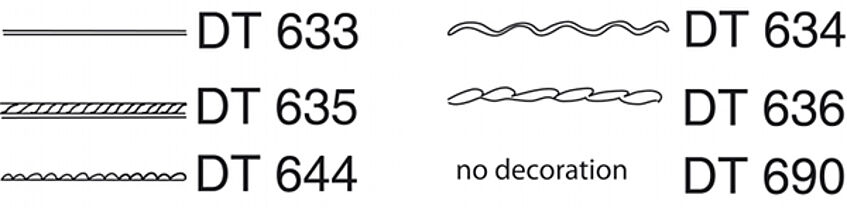

A good example of this combined approach and the potential it provides is the case of the so called “cylindrical vessels”, beautifully made containers for oils that apparently formed a major component of the burial assemblages of the early kings. Already Petrie recognized the potential this vessel type had for the purposes of dating based on the type of decoration the vessels had below the neck. Our own work is helping to refine these early results.

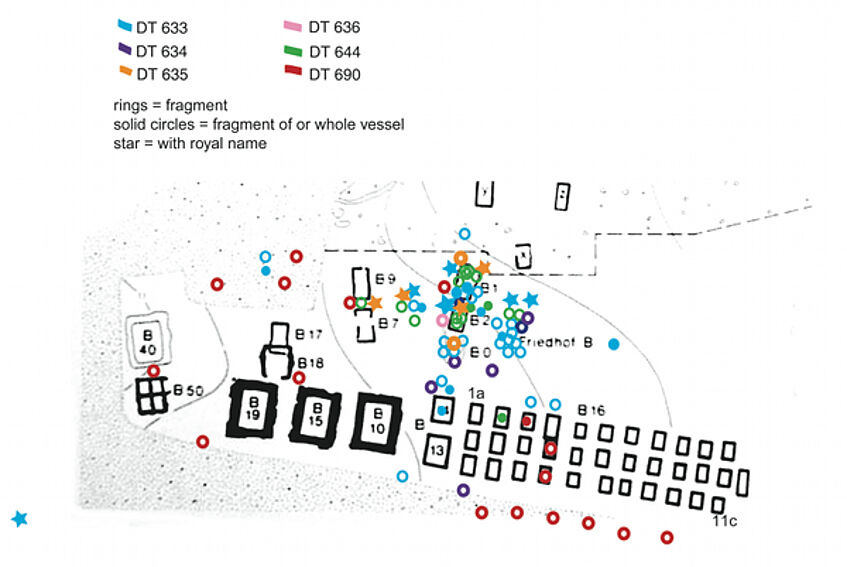

Fig. 6: Illustration of different decoration types of cylindrical vessels

In the B-Cemetery we were able to identify 6 different decoration types (DT) according to which the entirety of the diagnostic material was quantified. When these results are superimposed on a plan of the B Cemetery, it is possible to observe that particular types of decoration appear to be meaningfully associated with different areas of the cemetery. A range of decorated cylindrical vessels appear to be typical for the earliest parts of the cemetery when production was quite heterogeneous, while uniform and undecorated cylindrical vessels are probably to be chiefly associated with the latest tomb of the B Cemetery, that of Hor Aha. Micro-analysis of the fabrics shows that these latter cylinders were also made of a slightly less fine Marl fabric than the decorated cylinders. Undecorated cylinders coming from the western edge of the B Cemetery and possibly deriving from the tomb of Djer are in contrast made of a distinctive silt fabric.

Fig. 7: Distribution plan of cylindrical vessels with their decoration types

The case of the cylindrical vessels is not an isolated one and the same method is being applied to other vessel types. Most of these types are already known to us superficially from the old publications of Petrie, where only type drawings were published and the chief criterion of description was basic vessel shape. Our new research, therefore, is more interested in documenting and evaluating micro-variables in technology and materials, as well as quantitative analysis of details of vessel morphology to produce an ultimately much more complex, but much more accurate and diachronically sensitive snapshot of the pottery contents of the royal tombs.

Looking North

A final area of research that a study of the pottery from the B Cemetery opens up is foreign relations and trade during Dynasty 0 and early Dynasty 1. In the 2013 study season E.C. Köhler made a detailed analysis of more than 600 sherds, representing at least 30 vessels that were imported from the Near East. Based on their morphology and clay fabric it is possible to tell that these appear to have been traded from various places along the Levantine coast and hint at rich and extensive trade routes of which the Abydene kings were beneficiaries. This material will be included into a planned wider petrographic study of imports in Proto- and Early Dynastic Egypt that will provide an important database of scientific evidence for analysing the points of contact for early Egypt with its neighbours, and for the sychronisation of early Egyptian chronology with the dating systems currently used in the Levant.

Fig. 8: Imported vessel from the tomb of Aha

Selected Bibliography

Dreyer, G., 1998. Umm el-Qaab. Band 1: das prädynastische Königsgrab U-j und seine frühen Schriftzeugnisse. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Kairo 86. Mainz

Dreyer, G. et alii, 1991. Umm el-Qaab: Nachuntersuchungen im frühzeitlichen Königsfriedhof. 3./4. Vorbericht. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Kairo 46, 53-90

Dreyer, G. et alii, 1993. Umm el-Qaab: Nachuntersuchungen im frühzeitlichen Königsfriedhof. 5./6. Vorbericht. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Kairo 49, 23-62

Dreyer, G. et alii, 1996. Umm el-Qaab. Nachuntersuchungen im frühzeitlichen Königsfriedhof, 7./8. Vorbericht. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Kairo 52, 11-81

Dreyer, G. et alii, 1998. Umm el-Qaab. Nachuntersuchungen im frühzeitlichen Königsfriedhof, 9./10. Vorbericht. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Kairo 54, 77-167

Dreyer, G. et alii, 2000. Umm el-Qaab. Nachuntersuchungen im frühzeitlichen Königsfriedhof, 11./12. Vorbericht. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Institut, Kairo 56, 43-129

Dreyer, G. et alii, 2003. Umm el-Qaab: Nachuntersuchungen im frühzeitlichen Königsfriedhof. 13./14./15. Vorbericht. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Kairo 59, 67-138

Hartung, U., 2001. Umm el-Qaab. Band 2: Importkeramik aus dem Friedhof U in Abydos (Umm el-Qaab) und die Beziehungen Ägyptens zu Vorderasien im 4. Jahrtausend v.Chr. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Kairo 92. Mainz

Kaiser, W., 1981. Zu den Königsgräbern der 1. Dynastie in Umm el-Qaab. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Kairo 37, 247-254

Kaiser, W. - P. Grossmann, 1979. Umm el-Qaab. Nachuntersuchungen im frühzeitlichen Königsfriedhof: 1. Vorbericht. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Kairo 35, 155-163

Kaiser, W. - G. Dreyer, 1982. Umm el-Qaab. Nachuntersuchungen im frühzeitlichen Königsfriedhof: 2. Vorbericht. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Kairo 38, 211-269