Visualizing an Ancient Egyptian Queen - The Tomb of the 1st Dynasty Queen Meret-Neith at Abydos

(A project funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF and the German Research Foundation DFG, Project ID I-4688)

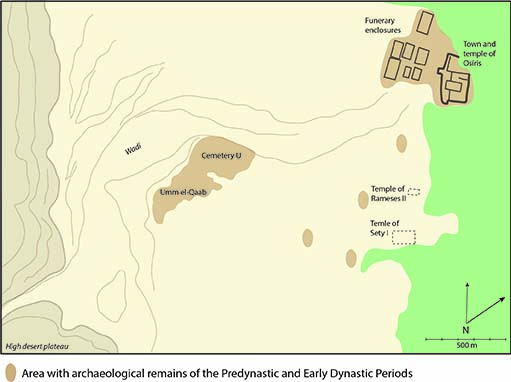

The site Abydos – Umm el-Qaab

Umm el-Qaab, looking at the rocky plateau in the south (Photo: E.C. Köhler)

Umm el-Qaab at the desert edge (Image: E.C. Köhler)

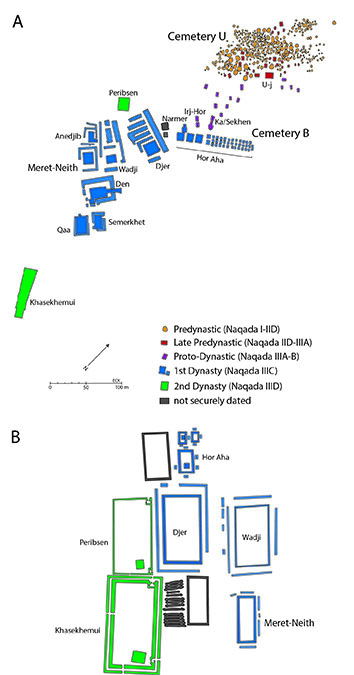

Royal tombs at Umm el-Qaab and their funerary enclosures in the North cemetery (Image: E.C. Köhler)

The site Abydos – Umm el-Qaab

The site of Umm el-Qaab is a large cemetery on the edge of the desert southwest of the ancient city of Abydos in Upper Egypt, where all of the kings of the 1st Dynasty and the last two kings of the 2nd Dynasty were buried.

The French Egyptologist Emile Amélineau first uncovered extensive parts of the area between 1895 and 1998. However, his methods were considered inadequate already in this early phase of Egyptian archaeology. For this reason, William Flinders Petrie, who had criticised the insufficient documentation, took over the concession for the excavations a short time later. During his first excavation in the winter of 1899-1900, the British archaeologist uncovered six royal tombs of the 1st Dynasty: those of the kings Wadji (tomb Z), Den (tomb T), Adjib (tomb X), Semerkhet (tomb U) and Qaa (tomb Q) as well as of queen Meret-Neith (tomb Y). He also produced the first general plan of the site. However, considering the short time for these achievements, it is not surprising that little has been documented and published in comparison to modern standards.

For this reason, the German Archaeological Institute initiated further excavations in the royal cemetery at Umm el-Qaab in 1978, which continue to this day. In the 2010s, Günter Dreyer had the overall plan of the site revised and completed. In this context, also the northeastern corner of Meret-Neith’s tomb was briefly cleared in 2011 and 2013.

In 2021, E. Christiana Köhler and her team finally started the complete excavation and documentation of the tomb complex of queen Meret-Neith according to modern standards to establish the chronological position and role of Meret-Neith within the 1st Dynasty and to better understand, visualise and archive her monumental tomb complex and the associated artefacts.

Queen Meret-Neith

During the 1st Dynasty, around 3000 BCE, Meret-Neith was one of the most influential women at the royal court. Archaeological and inscriptional sources have been interepreted to suggest that she may have been a daughter of Djer, the main wife of Wadji and the mother of King Den. However, she was probably not only a woman of royal descent who was supposed to guarantee the continuation of the royal bloodline but she also had considerable influence and power. She was the only woman who had her own tomb in the royal ancestral cemetery in Umm el-Qaab, which was in no way inferior in size, design and furnishings in comparison to those of her predecessors and descendants. Despite this, Meret-Neith's tomb, historical position, and rule have received little attention for a long time.

The new interdisciplinary project Visualizing an Ancient Egyptian Queen has set itself the task of changing this situation. The tomb complex is being re-excavated according to modern standards and documented archaeologically and photogrammetrically. The recovered artefacts are also analysed using the latest state-of-the-art methods. This also includes archaeological material from Petrie's excavations at Abydos, which are housed in different international museums today.

Tomb stela of queen Meret-Neith in the Egyptian Museum Cairo (JE34550, Photo: E.C. Köhler)

Meret-Neiths tomb, looking from the north-eastern corner (Photo: E.C. Köhler)

Tomb Architecture

The tomb complex is oriented along the local north-south axis, i.e. parallel to the Nile River, and is made of unfired mudbricks. The central part measures approximately 16.5 x 14.3 m and is entirely placed underground with the top of the walls just below the ancient desert surface. The maximum wall thickness is about 1.3 m. All the walls were bound by mud mortar and were originally plastered with mud.

The main chamber (Y-KK) is located at the centre of the tomb. It is most probably the chamber in which Meret-Neith was buried - although Petrie did not report any specific human remains here. Running parallel to the main chamber are eight elongated side chambers (Y-KK1 to Y-KK8) where the queen's numerous grave goods were presumably kept. This central area is surrounded by a rectangle of 41 subsidiary chambers, leaving a large gap in the southwestern corner.

Excavating the main chamber Y-KK (Photo: E.C. Köhler)

Packing finds (Photo: E.C. Köhler)

Searching for small artefacts with sieves (Photo: K. Mayer)

During the new excavations, the team observed evidence of different construction phases. For example, the exterior and interior walls of the central part appear to have been built around the same time, while most of the partition walls in the side chambers were constructed after that.

After the burials and grave goods had been deposited, the chambers were covered with wooden beams, mats and irregular layers of mudbricks and mud. A large tumulus of sand and debris was probably above the central area. The subsidiary chambers were probably covered by small mudbrick structures.

Main chamber Y-KK with partly burnt walls (Photo: F. Junge)

Uncovering and removing wood remains (Photo: E.C. Köhler)

Excavation of a partition wall (Photo: E.C. Köhler)

As is often observed in the royal necropolis, the central part of Meret-Neith's tomb and many of the artefacts were heavily affected by secondary burning. Some mudbrick walls were fired entirely through, and the sandy ground had turned into a hard, partially molten mass, suggesting long-lasting, very high temperatures. One research objective of the project is to determine the exact dating of this fire.

Photogrammetry

Concerns regarding the preservation and site management of the Umm el-Qaab site in general, and Meret-Neith’s tomb in particular, resulted in additional digital documentation of the royal tombs. Virtual Reality (VR) or Augmented Reality (AR) applications are therefore designed to protect the archaeological remains while at the same time making them accessible to visitors.

3D model of the tomb‘s central part (Image: P. Ferschin, B. Kovacs et al.)

Printed 3D model of the central tomb area with AR visualisation (Photo: F. Sövegjarto)

Photogrammetry has already been used as a valuable documentation method in various archaeological disciplines. Recording processes adapted to the circumstances are not invasive. They help to protect sensitive objects and allow for a highly accurate archaeological documentation without destruction.

In addition, the photogrammetry workflow can quickly capture a large amount of data, which is particularly important for large-scale sites and details. At the same time, the resulting large amounts of data can be easily processed with a relatively affordable computer infrastructure. The models created in this way can be easily shared, visualised, and processed in various applications.

Once the relevant parameters have been defined, this high-quality computed model geometry can immediatly generate representations of specific features that would take considerably more time using traditional documentation techniques (i.e., surveying, manual mapping on site).

An example is the generation of various arbitrary cross-sections and outlines of both architectural structures and artefacts. It is also possible to generate ortho-projections of arbitrary views for visualisation and further processing (measurements, tracing, etc.). The model can also serve as a basis for creating virtual or augmented realities.

Grave Goods

Thousands of Early Dynastic artefacts and ecofacts have already been found in the excavated areas. They include ceramic and stone vessels, mud and clay sealings, personal adornments, various objects made of wood, ivory, copper and different stones, as well as human, faunal and botanical remains. Their classification and analysis are ongoing.

Among the ceramic vessels, the so-called wine jars clearly dominate the inventory. They are followed in descending order by small-sized jars, ovoid jars of various sizes, globular to barrel-shaped vessels, cylindrical jars, bowls and plates of different sizes and designs, bread moulds and imported Levantine jars.

Sorting ceramic sherds (Photo: F. Junge)

Photographic documentation of an inscribed jar sealing (Photo: K. Mayer)

Small-sized ceramic jar (Photo: E.C. Köhler)

Wine Jars in KK-2

The side chamber Y-KK2 in the north-eastern corner of the main tomb originally contained many wine jars. Petrie had already excavated this chamber in 1899 but left several wine jars in their original position. Also, Dreyer and his team cleared the northeastern corner of the tomb for its integration into the overall site map, but they did not move the vessels. At that time, they found about 50 wine jars still in a primary position, of which about 20 were intact and held their clay sealings. Soon after that, the site was looted and the chamber was partially emptied; it was subsequently backfilled by our colleagues of the inspectorate.

When the chamber was finally excavated again in 2021, its lowermost layer of fill material comprised a vessel deposit that was most probably in its primary position. This deposit included 24 intact and complete wine jars, of which three still held their intact mud sealings. The vessels were positioned upright in a cluster at the chamber's centre.

Intact wine jars in the side chamber Y-KK2 in primary position (Photo: E.C. Köhler)

Documentation of the wine jars at the dig house (Photo: F. Junge)

Wine jar contents: grape seeds (Photo E.C. Köhler)

The discovered wine jars represent typical 1st Dynasty types. They were either made of Nile silt, marl clay or mixed clays. A whitish layer of calcareous sinter often covered their exterior surfaces and cord impressions were still visible. The interior of twelve specimens showed distinct horizontal incrustations indicating that the vessels had been filled to the top with liquids at the time of deposition, which only gradually evaporated. Each of the more than 50 documented wine jars had at least one pre-firing potmark representing various shapes and designs.

Small Finds

In the present project, the term small finds is applied to all artefacts except pottery vessels.

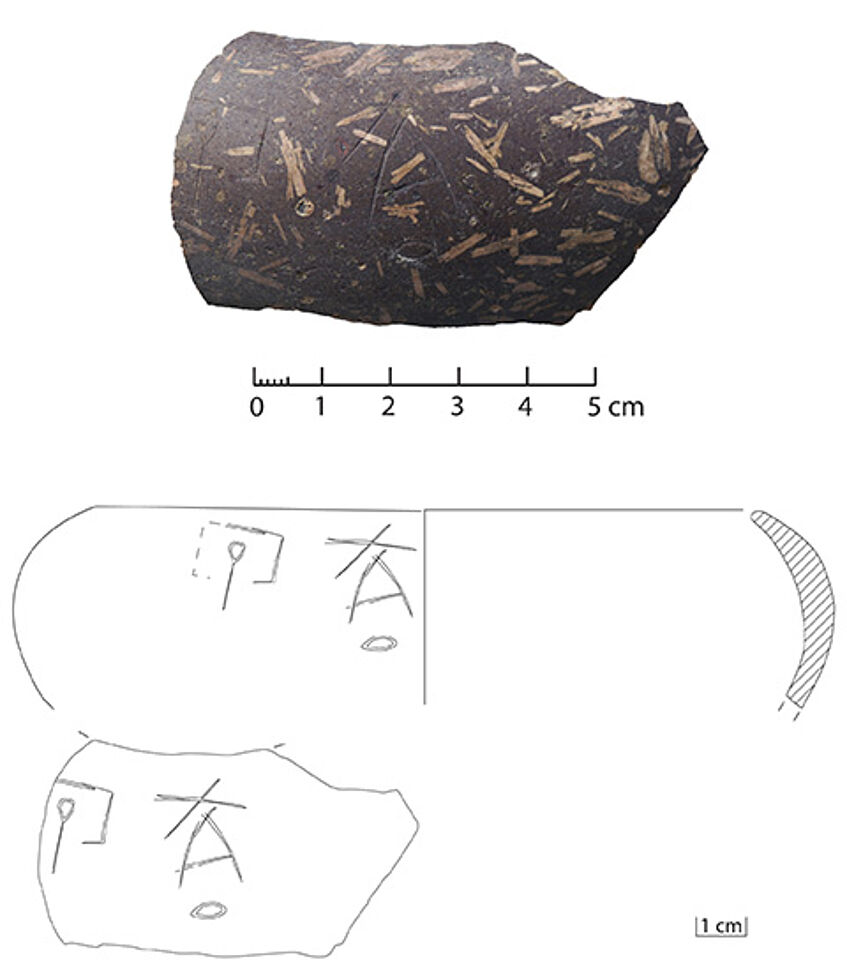

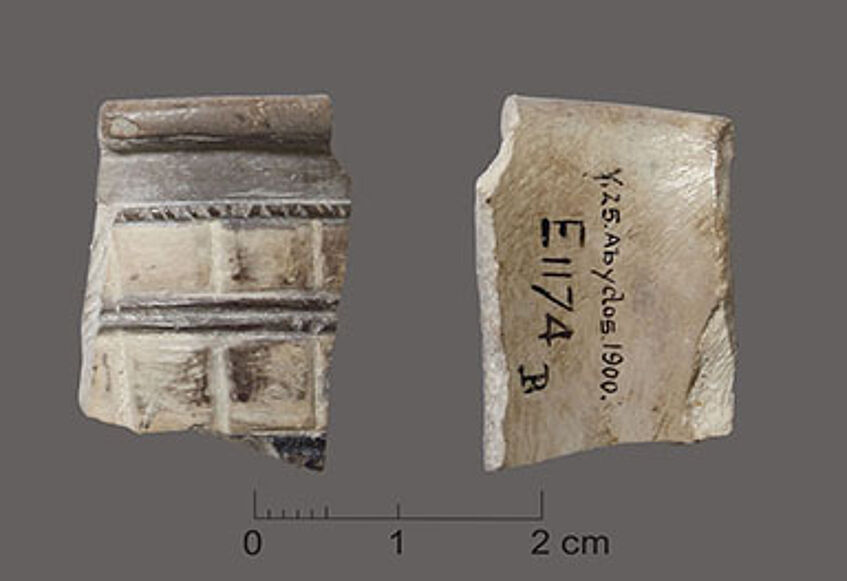

In the tomb of Meret-Neith, many such small finds are represented by stone vessels, which were often made of calcite and siltstone. Most documented shapes are cylindrical jars, bowls and plates. Some intact or complete vessels have survived Petrie's excavations and can be seen in different museum collections today. Furthermore, several stone vessel fragments bear inscriptions, some of which exhibit the name of queen Meret-Neith.

Rim fragment of an incised stone vessel from Meret-Neiths tomb (Photo and Drawing: E.C. Köhler)

Conical mud sealing with seal impression at the Ashmolean Museum (E.2854, Photo: E.C. Köhler, curtesy Ashmolean Museum)

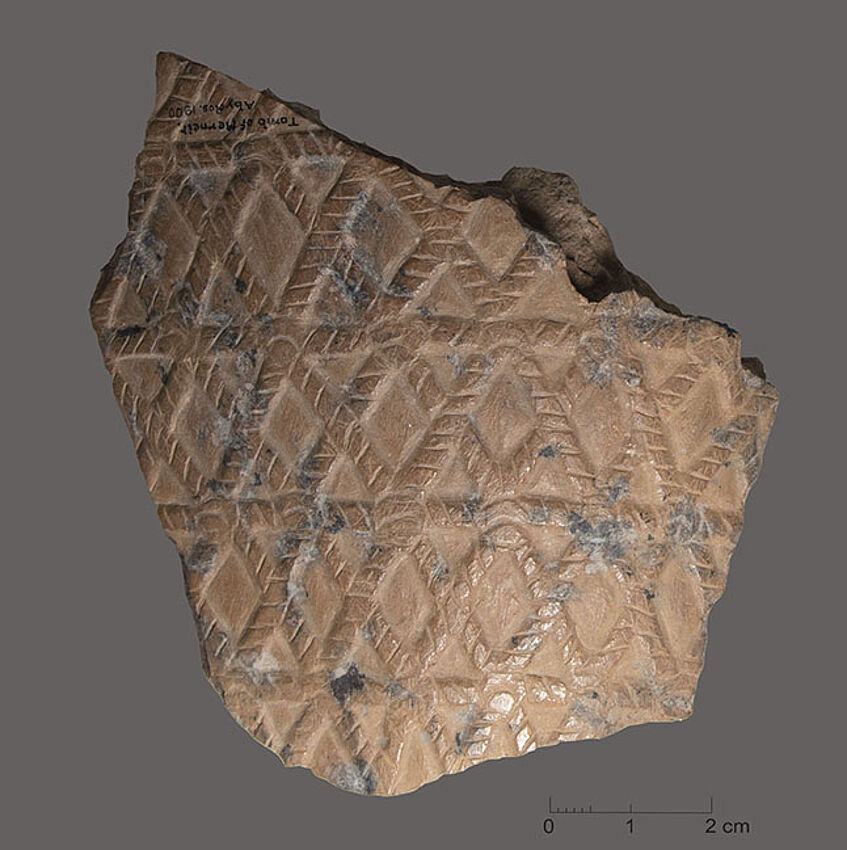

Decorated limestone vessel fragment at the Ashmolean Museum (E.1169, Photo: E.C. Köhler, curtesy Ashmolean Museum)

The second largest category of finds is associated with sealing pottery vessels and other containers: mud or clay sealings and stoppers, partly with seal impressions. Petrie and Kaplony have already worked on some of these seal impressions, but hundreds of new finds have been recorded now.

Another important group is comprised of furniture fragments of wood and ivory. The richly decorated pieces, albeit often heavily fragmented and sometimes burnt, bear witness to a rich furniture inventory. Also worth mentioning is an ivory vessel, of which several fragments were identified both at the Ashmolean Museum and during earlier and the current excavation work.

Rim fragments of an ivory vessel from the Ashmolean Museum (E.1174, Photo: E.C. Köhler, curtesy Ashmolean Museum)

Base fragment from the same vessel from recent excavations (K23-1284, Photo: E. C. Köhler)

Scientific Analysis

The Meret-Neith Project aims to establish a high standard in the application of archaeological science in Egyptian archaeology, and indeed, the scope and research questions of the project are greatly enhanced owing to the application of various archaeological science methods.

The project applies analytical techniques both to suitable materials from the current excavations as well as to materials that Petrie excavated at the turn of the 20th century.

Radiocarbon dating helps to better reconstruct the absolute chronology of Meret-Neith. A wide variety of short-lived organic materials recovered from her tomb have been selected for analysis, including organic contents of ceramic vessels (fatty substances, plant remains), remains of rope and wood from both the central part and the subsidiary chambers.

Organic residue analysis is carried out on selected vessels from Meret-Neith's funerary assemblage to determine what was contained in the vessels. Residue analysis is particularly powerful when used in combination with archaeobotanical analysis.

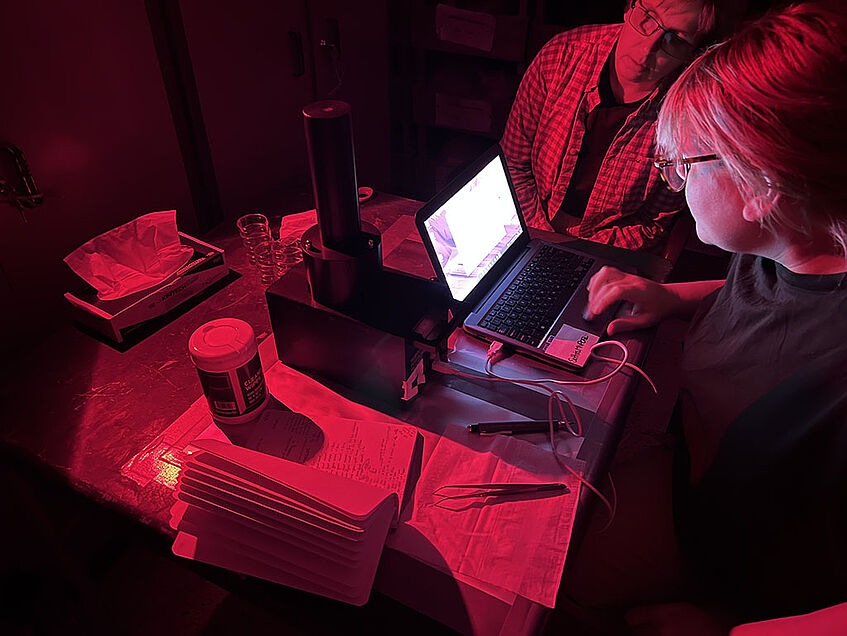

Luminescence analysis assists in chronometrically dating ceramic and mud artefacts from museum collections. In the field, portable luminescence profiling is applied to reconstruct site taphonomy, relative chronology architectural construction phases and the relationship between archaeological deposits within the tomb. This profiling allows for a way to rapidly disentangle complex past activities in the field.

Sampling for portable luminescence analysis (Photo: E.C. Köhler)

pOSL analysis in a light-proof space at the dig house (Photo: E.C. Köhler)

Pottery vessel with remains of rope (Photo: E.C. Köhler)

Former and current team members

E. Christiana Köhler (University of Vienna): Project leader

Friederike Junge (University of Vienna): Deputy director, Pottery

Mathilde Minotti (University of Vienna): Deputy director, Small finds

Amber Hood (Lund Universität): Deputy director, Archaeological Science

Peter Ferschin (University of Technology Vienna): Photogrammetry, Digital Architecture

Bálint Kovács (University of Technology Vienna): Photogrammetry, Computer Science

Emanuele Casini: Archaeology

Mary Ownby: Petrography

Karl-Johann Mayer: Photography

Lara Borchardt, Ahmed el-Gamal, Magdalena Greshake, Johannes Grimm, Alexander Haidegger, Allison McCoskey, Alexandra Pavel, Sara Scavuzzo, Fabian Seiser, Florian Sövegjarto, Julia Strasser: Student assistants

Bakri Badri, Ibrahim Abulhamdi, Alaa Ali, Abdelgabbar Mohamed, Hani Kher, Karem Serag: Excavation foreman

Breakfast in the dig house (Photo: E.C. Köhler)

Looking at the rock desert at Umm el-Qaab (Photo: E.C. Köhler)

Cooperation partners

Dr. Ashraf Okasha, Dr. Mohamed Naguib (Directors of the SCA inspectorates at Sohag and Balyana)

Mr. Ahmed Abdelkader Abdellatif Abdelrahman, Mr. Hany Mohamed Ahmed Abdelhalim and Ms. Afaf Abdelhamid Mahmoud Mohamed, Mr. Amgad Faruk Sharubi, Mr. Hamdi Khalifa Eissa Abdelkader and Mrs. Amal Mohamed Emara Mohamed (SCA Inspectors)

Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (MoTA)

Dr. Dietrich Raue (German Archaeological Institute Cairo) Project description in the Newsroom

Acknowledgements and Project Funding

The Meret Neith project has received financial funding from the following institutions: DFG, FWF, TUW and the University of Vienna. We are also grateful to the many student assistants who have physically supported the project.

We also thank our colleagues and the First Director of the DAI Cairo, Dr. Dietrich Raue, for the excellent cooperation. Furthermore, we express our gratitude to the colleagues at the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities and the Supreme Council of Antiquities in Egypt, Dr Mohamed Naguib (Director of the Inspectorate in el-Balyana) and Dr Ashraf Okasha (Director of the Inspectorate in Sohag), and their staff for their approvals and great cooperation.

Furthermore, we would like to thank our colleagues at the following museums and institutions for permitting the study and publication of materials from Petrie’s excavations: Ägyptisches Museum Bonn, Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung Berlin, Ashmolean Museum Oxford, Bexhill Museum, Bolton Museum, British Museum London, Hunterian Museum Glasgow, , ISAC Museum Chicago, Manchester Museum, Musée Art & Histoire Brüssel, Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology London, Pitt Rivers Museum Oxford, World Museum Liverpool.

Selected Bibliography

In press

E.C. Köhler, P. Ferschin, A. Hood, F. Junge, B. Kovacs and M. Minotti, A preliminary report of new archaeological fieldwork at the tomb of queen Meret-Neith of the 1st Dynasty at Abydos - Umm el-Qaab, Egypt and Levant.

E.C. Köhler, Visualizing an Ancient Egyptian Queen: the Tomb of Meret-Neith of the 1st dynasty at Abydos – Umm el-Qaab revisited, in: Tristant, Y. (Hg.), Egypt at its Origins 7, Orientalia Lovanensia Analecta, Leuven 2024, 371–393.

Project-based Theses

2022

S. Treccarichi Scavuzzo, Immersive experience of ancient architectural heritage and related historical events – Reconstruction and visualisation of the fire incident at the tomb of first Dynasty Egyptian Queen Meret-Neith in Abydos [Diploma Thesis, Technische Universität Wien 2022]. reposiTUm

2023

F. Sövegjarto, Augmentierte Präsentation historischer Architektur am Beispiel des Grabes von Meret Neith in Abydos [Diploma Thesis, Technische Universität Wien 2023]. reposiTUm